After reading this section, you should understand the following:

Unless one operates a business completely alone, it is likely they will need the help of others. An "agent" is a person who acts in the name of and on behalf of another, having been given and assumed some degree of authority to do so. Most organized human activity—and virtually all commercial activity—is carried on through agency. No corporation would be possible, even in theory, without such a concept. We might say “General Motors is building cars in China,” for example, but we can’t shake hands with General Motors. “The General,” as people say, exists and works through agents. Likewise, partnerships and other business organizations rely extensively on agents to conduct their business. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that agency is the cornerstone of enterprise organization. In a partnership each partner is a general agent, while under corporation law the officers and all employees are agents of the corporation.

The existence of agents does not, however, require a whole new law of torts or contracts. A tort is no less harmful when committed by an agent; a contract is no less binding when negotiated by an agent. What does need to be taken into account, though, is the manner in which an agent acts on behalf of his principal and toward a third party.

The general agentSomeone authorized to transact every kind of business for the principal. possesses the authority to carry out a broad range of transactions in the name and on behalf of the principal. The general agent may be the manager of a business or may have a more limited but nevertheless ongoing role—for example, as a purchasing agent or as a life insurance agent authorized to sign up customers for the home office. In either case, the general agent has authority to alter the principal’s legal relationships with third parties. One who is designated a general agent has the authority to act in any way required by the principal’s business. To restrict the general agent’s authority, the principal must spell out the limitations explicitly, and even so the principal may be liable for any of the agent’s acts in excess of his authority.

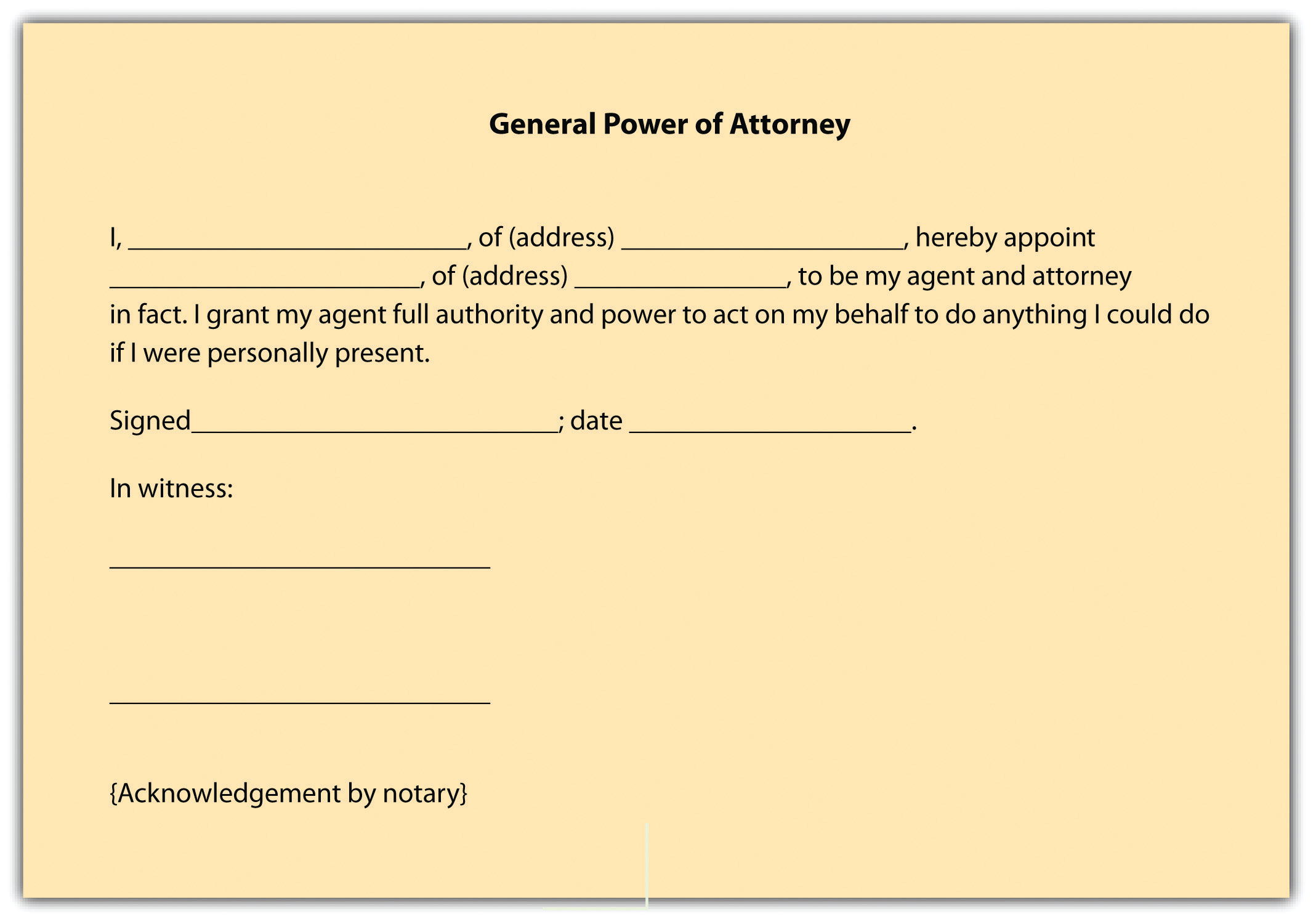

Normally, the general agent is a business agent, but there are circumstances under which an individual may appoint a general agent for personal purposes. One common form of a personal general agent is the person who holds another’s power of attorney. This is a delegation of authority to another to act in his stead; it can be accomplished by executing a simple form, such as the one shown in Figure 57.1 "General Power of Attorney". Ordinarily, the power of attorney is used for a special purpose—for example, to sell real estate or securities in the absence of the owner. But a person facing a lengthy operation and recuperation in a hospital might give a general power of attorney to a trusted family member or friend.

Figure 57.1 General Power of Attorney

The special agentAn agent hired by contract to carry out specifically stated activities. is one who has authority to act only in a specifically designated instance or in a specifically designated set of transactions. For example, a real estate broker is usually a special agent hired to find a buyer for the principal’s land. Suppose Sam, the seller, appoints an agent Alberta to find a buyer for his property. Alberta’s commission depends on the selling price, which, Sam states in a letter to her, “in any event may be no less than $150,000.” If Alberta locates a buyer, Bob, who agrees to purchase the property for $160,000, her signature on the contract of sale will not bind Sam. As a special agent, Alberta had authority only to find a buyer; she had no authority to sign the contract.

An agent whose reimbursement depends on his continuing to have the authority to act as an agent is said to have an agency coupled with an interestAn agency in which the agent has an interest in the property regarding which he or she is acting on the principal’s behalf. if he has a property interest in the business. A literary or author’s agent, for example, customarily agrees to sell a literary work to a publisher in return for a percentage of all monies the author earns from the sale of the work. The literary agent also acts as a collection agent to ensure that his commission will be paid. By agreeing with the principal that the agency is coupled with an interest, the agent can prevent his own rights in a particular literary work from being terminated to his detriment.

The agency relationship can be created in two ways: by agreement (expressly) or by operation of law (constructively or impliedly).

Most agencies are created by contract. Thus the general rules of contract law covered in the prior chapter govern the law of agency. But agencies can also be created without contract, by agreement. Therefore, three contract principles are especially important: the first is the requirement for consideration, the second for a writing, and the third concerns contractual capacity.

Agencies created by consent—agreement—are not necessarily contractual. It is not uncommon for one person to act as an agent for another without consideration. For example, Abe asks Byron to run some errands for him: to buy some lumber on his account at the local lumberyard. Such a gratuitous agencyAn agency where the agent receives no compensation. gives rise to no different results than the more common contractual agency.

Most oral agency contracts are legally binding; the law does not require that they be reduced to writing. In practice, many agency contracts are written to avoid problems of proof. And there are situations where an agency contract must be in writing: (1) if the agreed-on purpose of the agency cannot be fulfilled within one year or if the agency relationship is to last more than one year; (2) in many states, an agreement to pay a commission to a real estate broker; (3) in many states, authority given to an agent to sell real estate; and (4) in several states, contracts between companies and sales representatives.

Even when the agency contract is not required to be in writing, contracts that agents make with third parties often must be in writing. Thus Section 2-201 of the Uniform Commercial Code specifically requires contracts for the sale of goods for the price of five hundred dollars or more to be in writing and “signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought or by his authorized agent.”

A contract is void or voidable when one of the parties lacks capacity to make one. If both principal and agent lack capacity—for example, a minor appoints another minor to negotiate or sign an agreement—there can be no question of the contract’s voidability. But suppose only one or the other lacks capacity. Generally, the law focuses on the principal. If the principal is a minor or otherwise lacks capacity, the contract can be avoided even if the agent is fully competent. There are, however, a few situations in which the capacity of the agent is important. Thus a mentally incompetent agent cannot bind a principal.

Most agencies are made by contract, but agency also may arise impliedly or apparently.

In areas of social need, courts have declared an agency to exist in the absence of an agreement. The agency relationship then is said to have been implied “by operation of law.” Children in most states may purchase necessary items—food or medical services—on the parent’s account. Long-standing social policy deems it desirable for the head of a family to support his dependents, and the courts will put the expense on the family head in order to provide for the dependents’ welfare. The courts achieve this result by supposing the dependent to be the family head’s agent, thus allowing creditors to sue the family head for the debt.

Implied agencies also arise where one person behaves as an agent would and the “principal,” knowing that the “agent” is behaving so, acquiesces, allowing the person to hold himself out as an agent. Such are the basic facts in Weingart v. Directoire Restaurant, Inc. in Section 38.3.1 "Creation of Agency: Liability of Parent for Contracts Made by “Agent” Child".

Suppose Arthur is Paul’s agent, employed through October 31. On November 1, Arthur buys materials at Lumber Yard—as he has been doing since early spring—and charges them to Paul’s account. Lumber Yard, not knowing that Arthur’s employment terminated the day before, bills Paul. Will Paul have to pay? Yes, because the termination of the agency was not communicated to Lumber Yard. It appeared that Arthur was an authorized agent. Thus, principals such as business owners need to take care they do not create the impression to third parties that authority exists for the agents to act, otherwise they may find they have inadvertantly created agency power and will be bound by the actions of the agent, whether or not they gave the agent express authority to act.If a rogue agent binds the principal under apparent authority, although the principal will be bound by the agent's actions, the agent will be liable to the principal for violating the agency relationships.

The agent owes the principal duties in two categories: the fiduciary duty and a set of general duties imposed by agency law. But these general duties are not unique to agency law; they are duties owed by any employee to the employer.

In a nonagency contractual situation, the parties’ responsibilities terminate at the border of the contract. There is no relationship beyond the agreement. This literalist approach is justified by the more general principle that we each should be free to act unless we commit ourselves to a particular course.

But the agency relationship is more than a contractual one, and the agent’s responsibilities go beyond the border of the contract. Agency imposes a higher duty than simply to abide by the contract terms. It imposes a fiduciary dutyThe duty of an agent to act always in the best interest of the principal, to avoid self-dealing.. The law infiltrates the contract creating the agency relationship and reverses the general principle that the parties are free to act in the absence of agreement. As a fiduciary of the principal, the agent stands in a position of special trust. His responsibility is to subordinate his self-interest to that of his principal. The fiduciary responsibility is imposed by law. The absence of any clause in the contract detailing the agent’s fiduciary duty does not relieve him of it. The duty contains several aspects.

A fiduciary may not lawfully profit from a conflict between his personal interest in a transaction and his principal’s interest in that same transaction. A broker hired as a purchasing agent, for instance, may not sell to his principal through a company in which he or his family has a financial interest. The penalty for breach of fiduciary duty is loss of compensation and profit and possible damages for breach of trust.

To further his objectives, a principal will usually need to reveal a number of secrets to his agent—how much he is willing to sell or pay for property, marketing strategies, and the like. Such information could easily be turned to the disadvantage of the principal if the agent were to compete with the principal or were to sell the information to those who do. The law therefore prohibits an agent from using for his own purposes or in ways that would injure the interests of the principal, information confidentially given or acquired. This prohibition extends to information gleaned from the principal though unrelated to the agent’s assignment: “[A]n agent who is told by the principal of his plans, or who secretly examines books or memoranda of the employer, is not privileged to use such information at his principal’s expense.” Restatement (Second) of Agency, Section 395. Nor may the agent use confidential information after resigning his agency. Though he is free, in the absence of contract, to compete with his former principal, he may not use information learned in the course of his agency, such as trade secrets and customer lists.

In addition to fiduciary responsibility (and whatever special duties may be contained in the specific contract) the law of agency imposes other duties on an agent. These duties are not necessarily unique to agents: a nonfiduciary employee could also be bound to these duties on the right facts.

An agent is usually taken on because he has special knowledge or skills that the principal wishes to tap. The agent is under a legal duty to perform his work with the care and skill that is “standard in the locality for the kind of work which he is employed to perform” and to exercise any special skills, if these are greater or more refined than those prevalent among those normally employed in the community. In short, the agent may not lawfully do a sloppy job.Restatement (Second) of Agency, Section 379.

In the absence of an agreement, a principal may not ordinarily dictate how an agent must live his private life. An overly fastidious florist may not instruct her truck driver to steer clear of the local bar on his way home from delivering flowers at the end of the day. But there are some jobs on which the personal habits of the agent may have an effect. The agent is not at liberty to act with impropriety or notoriety, so as to bring disrepute on the business in which the principal is engaged. A lecturer at an antialcohol clinic may be directed to refrain from frequenting bars. A bank cashier who becomes known as a gambler may be fired.

The agent must keep accurate financial records, take receipts, and otherwise act in conformity to standard business practices.

This duty states a truism but is one for which there are limits. A principal’s wishes may have been stated ambiguously or may be broad enough to confer discretion on the agent. As long as the agent acts reasonably under the circumstances, he will not be liable for damages later if the principal ultimately repudiates what the agent has done: “Only conduct which is contrary to the principal’s manifestations to him, interpreted in light of what he has reason to know at the time when he acts,…subjects the agent to liability to the principal.” Restatement (Second) of Agency, Section 383.

The principal says to the agent, “Keep working until the job is done.” The agent is not obligated to go without food or sleep because the principal misapprehended how long it would take to complete the job. Nor should the agent continue to expend the principal’s funds in a quixotic attempt to gain business, sign up customers, or produce inventory when it is reasonably clear that such efforts would be in vain.

As a general rule, the agent must obey reasonable directions concerning the manner of performance. What is reasonable depends on the customs of the industry or trade, prior dealings between agent and principal, and the nature of the agreement creating the agency. A principal may prescribe uniforms for various classes of employees, for instance, and a manufacturing company may tell its sales force what sales pitch to use on customers. On the other hand, certain tasks entrusted to agents are not subject to the principal’s control; for example, a lawyer may refuse to permit a client to dictate courtroom tactics.

The fiduciary relationship of agent to principal does not run in reverse—that is, the principal is not the agent’s fiduciary. Nevertheless, the principal has a number of contractually related obligations toward his agent.

These duties are analogues of many of the agent’s duties that we have just examined. In brief, a principal has a duty “to refrain from unreasonably interfering with [an agent’s] work.” Restatement (Second) of Agency, Section 434. The principal is allowed, however, to compete with the agent unless the agreement specifically prohibits it. The principal has a duty to inform his agent of risks of physical harm or pecuniary loss that inhere in the agent’s performance of assigned tasks. Failure to warn an agent that travel in a particular neighborhood required by the job may be dangerous (a fact unknown to the agent but known to the principal) could under common law subject the principal to a suit for damages if the agent is injured while in the neighborhood performing her job. A principal is obliged to render accounts of monies due to agents; a principal’s obligation to do so depends on a variety of factors, including the degree of independence of the agent, the method of compensation, and the customs of the particular business. An agent’s reputation is no less valuable than a principal’s, and so an agent is under no obligation to continue working for one who sullies it.

The principal is liable on an agent’s contract only if the agent was authorized by the principal to make the contract. Such authority is express, implied, or apparent. Express means made in words, orally or in writing; implied means the agent has authority to perform acts incidental to or reasonably necessary to carrying out the transaction for which she has express authority. Apparent authority arises where the principal gives the third party reason to believe that the agent had authority. The reasonableness of the third party’s belief is based on all the circumstances—all the facts. Even if the agent has no authority, the principal may, after the fact, ratify the contract made by the agent.

The principal will be liable for the employee’s torts in two circumstances: first, if the principal was directly responsible, as in hiring a person the principal knew or should have known was incompetent or dangerous; second, if the employee committed the tort in the scope of business for the principal. This is the master-servant doctrine or respondeat superior. It imposes vicarious liability on the employer: the master (employer) will be liable if the employee was in the zone of activity creating a risk for the employer (“zone of risk” test), that is—generally—if the employee was where he was supposed to be, when he was supposed to be there, and the incident arose out of the employee’s interest (however perverted) in promoting the employer’s business.

Special cases of vicarious liability arise in several circumstances. For example, the owner of an automobile may be liable for torts committed by one who borrows it, or if it is—even if indirectly—used for family purposes. Parents are, by statute in many states, liable for their children’s torts. Similarly by statute, the sellers and employers of sellers of alcohol or adulterated or short-weight foodstuffs may be liable. The employer of one who commits a crime is not usually liable unless the employer put the employee up to the crime or knew that a crime was being committed. But some prophylactic statutes impose liability on the employer for the employee’s crime—even if the employee had no intention to commit it—as a means to force the employer to prevent such actions.

A person is always liable for her own torts, so an agent who commits a tort is liable; if the tort was in the scope of employment the principal is liable too. Unless the principal put the agent up to committing the tort, the agent will have to reimburse the principal. An agent is not generally liable for contracts made; the principal is liable. But the agent will be liable if he is undisclosed or partially disclosed, if the agent lacks authority or exceeds it, or, of course, if the agent entered into the contract in a personal capacity.

Agencies terminate expressly or impliedly or by operation of law. An agency terminates expressly by the terms of the agreement or mutual consent, or by the principal’s revocation or the agent’s renunciation. An agency terminates impliedly by any number of circumstances in which it is reasonable to assume one or both of the parties would not want the relationship to continue. An agency will terminate by operation of law when one or the other party dies or becomes incompetent, or if the object of the agency becomes illegal. However, an agent may have apparent lingering authority, so the principal, upon termination of the agency, should notify those who might deal with the agent that the relationship is severed.

An agent is one who acts on behalf of another. Many transactions are conducted by agents so acting. All corporate transactions, including those involving governmental organizations, are so conducted because corporations cannot themselves actually act; they are legal fictions. Agencies may be created expressly, impliedly, or apparently.

Principals may be responsible for the actions of their agents, whether in contract (when the agent is acting with authority, including apparent authrority) or tort (e.g., when the agent was acting under the scope of the business of the principal).