During the course of the past seventy years, a substantial debate has been conducted, often in shrill terms, about the legitimacy of administrative lawmaking. One criticism is that agencies are “captured” by the industry they are directed to regulate. Another is that they overregulate, stifling individual initiative and the ability to compete. During the 1960s and 1970s, a massive outpouring of federal law created many new agencies and greatly strengthened the hands of existing ones. In the late 1970s during the Carter administration, Congress began to deregulate American society, and deregulation increased under the Reagan administration. But the accounting frauds of WorldCom, Enron, and others led to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, and the financial meltdown of 2008 has led to reregulation of the financial sector. In the 2010s, the Trump administration set about a large scheme of government deregulation, citing concerns that regulation impaired business productivity.

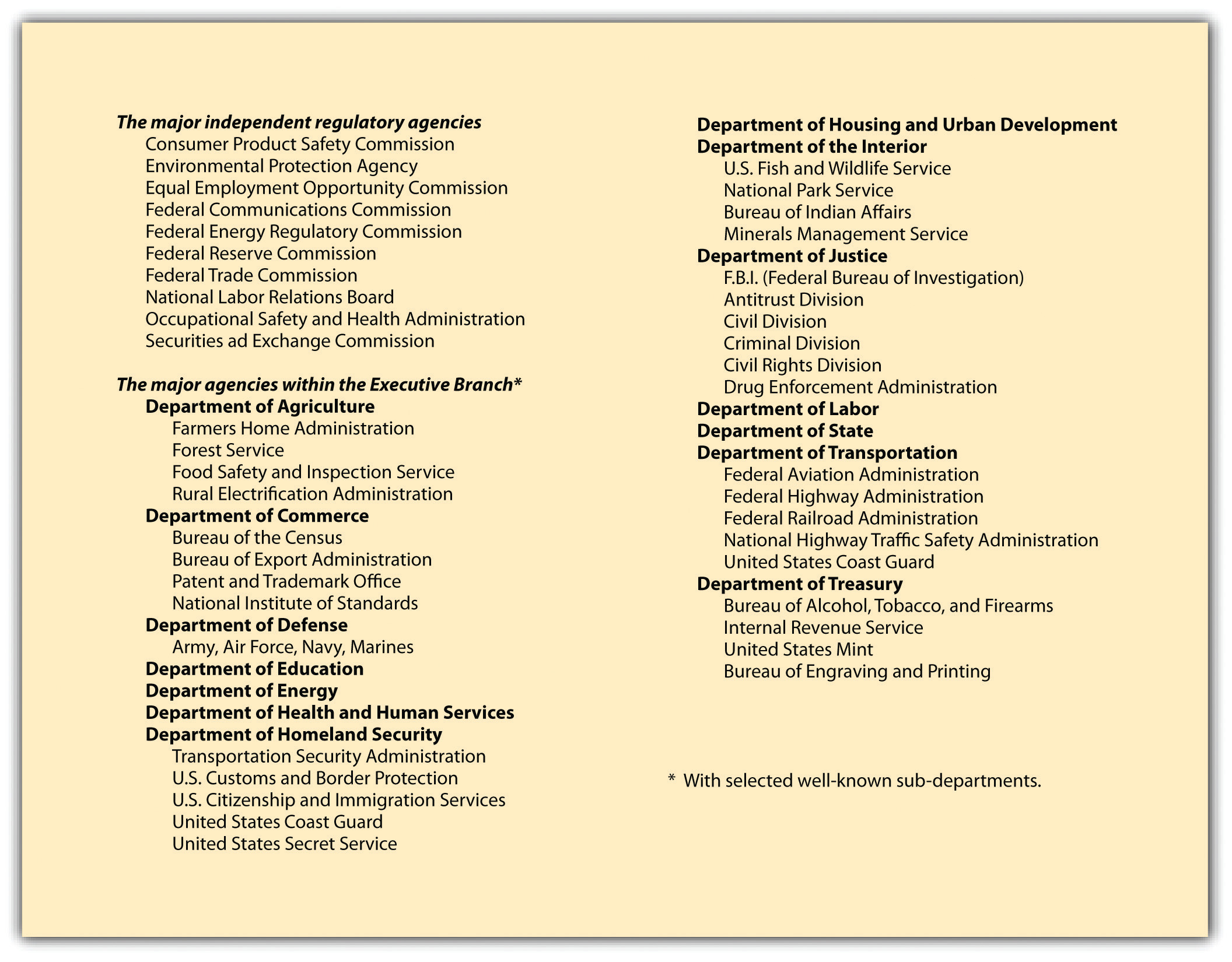

Administrative agencies are the focal point of controversy because they are policy-making bodies, incorporating facets of legislative, executive, and judicial power in a hybrid form that fits uneasily at best in the framework of American government (see Figure 5.1 "Major Administrative Agencies of the United States"). They are necessarily at the center of tugging and hauling by the legislature, the executive branch, and the judiciary, each of which has different means of exercising political control over them. In early 1990, for example, the Bush administration approved a Food and Drug Administration regulation that limited disease-prevention claims by food packagers, reversing a position by the Reagan administration in 1987 permitting such claims.

Figure 5.1 Major Administrative Agencies of the United States

Congress can always pass a law repealing a regulation that an agency promulgates. Because this is a time-consuming process that runs counter to the reason for creating administrative bodies, it happens rarely. Another approach to controlling agencies is to reduce or threaten to reduce their appropriations. By retaining ultimate control of the purse strings, Congress can exercise considerable informal control over regulatory policy.

The president (or a governor, for state agencies) can exercise considerable control over agencies that are part of his cabinet departments and that are not statutorily defined as independent. Federal agencies, moreover, are subject to the fiscal scrutiny of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), subject to the direct control of the president. Agencies are not permitted to go directly to Congress for increases in budget; these requests must be submitted through the OMB, giving the president indirect leverage over the continuation of administrators’ programs and policies.

Administrative agencies are creatures of law and like everyone else must obey the law. The courts have jurisdiction to hear claims that the agencies have overstepped their legal authority or have acted in some unlawful manner.

Courts are unlikely to overturn administrative actions, often believing that the agencies are better situated to judge their own jurisdiction and are experts in rulemaking for those matters delegated to them by Congress. In a famous case referred to as Chevron,Chevron, USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 US 837 (1984) the United States Supreme Court established the doctine of "Chevron deference." This doctrine states that courts should defer to how agencies interpret statutues. If Congress did not speak clearly to an issue, courts must defer to the agency's "permissible" or "reasonable" interpretation of the statute. We will see this in environmental law with the case Energy Corp. v. Riverkeeper, in which a plaintiff challenged the EPA's interpretation of the statutory word "best": does "best" mean absolute best or best taking cost into account?

Administrative agencies are given unusual powers: to legislate, investigate, and adjudicate. But these powers are limited by executive and legislative controls and by judicial review.